VI: Hans Winterberg – Sudeten-Suite – Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano (1963/64)

Please select a title to play

I: Hans Winterberg – Trio for Clarinet, Cello and Piano (1950)

I: Hans Winterberg – Trio for Clarinet, Cello and Piano (1950)

01 Leicht fließend

I: Hans Winterberg – Trio for Clarinet, Cello and Piano (1950)

02 Andante sostenuto

I: Hans Winterberg – Trio for Clarinet, Cello and Piano (1950)

03 Tempo di Menuetto

I: Hans Winterberg – Trio for Clarinet, Cello and Piano (1950)

04 Allegro barbaro

II: Hans Winterberg – Suite for Violin and Piano (1942)

05 Allegro moderato (poco agitato)

II: Hans Winterberg – Suite for Violin and Piano (1942)

06 Molto moderato

II: Hans Winterberg – Suite for Violin and Piano (1942)

07 Agitato

III: Hans Winterberg – Suite for Trumpet and Piano No. 2 (1952)

08 Lebhaft bewegt

III: Hans Winterberg – Suite for Trumpet and Piano No. 2 (1952)

09 Andante moderato

III: Hans Winterberg – Suite for Trumpet and Piano No. 2 (1952)

10 Allegro moderato ma energico

IV: Hans Winterberg – "Dort und Hier" for Soprano and Piano Trio (1936/37)

11 Madonna mit den Krähen

IV: Hans Winterberg – "Dort und Hier" for Soprano and Piano Trio (1936/37)

12 Nach dem Tode

IV: Hans Winterberg – "Dort und Hier" for Soprano and Piano Trio (1936/37)

13 Dort und Hier

IV: Hans Winterberg – "Dort und Hier" for Soprano and Piano Trio (1936/37)

14 Der Schneefall

V: Hans Winterberg – Suite for Clarinet in B flat and Piano (1944)

15 Con moto

V: Hans Winterberg – Suite for Clarinet in B flat and Piano (1944)

16 Zwischenspiel

V: Hans Winterberg – Suite for Clarinet in B flat and Piano (1944)

17 Nachspiel

VI: Hans Winterberg – Sudeten-Suite – Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano (1963/64)

18 Rund um die Schneekoppe

VI: Hans Winterberg – Sudeten-Suite – Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano (1963/64)

19 Rund um den Plöckenstein

VI: Hans Winterberg – Sudeten-Suite – Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano (1963/64)

20 Elbe-Quellen

....................................................................................................

Nominated for the German Record Critics' Award in the "Chamber Music" category (Quarterly Critic's Choice – Long List 2/2025)

There and Here

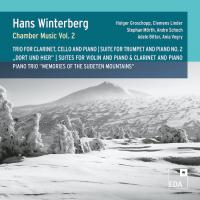

With this second volume of our series dedicated to the chamber music of Hans Winterberg, we not only want to bring a number of further outstanding pieces by this Prague composer back into musical life, but above all also to continue addressing a complex, little-known chapter in the European cultural history of the twentieth century. In contrast to volume 1 (EDA 51), where for dramaturgical reasons we arranged the works backwards on the timeline according to the year of composition, we present them here in a historical and topographical zigzag course, as suggested by the motto "There and Here" under which we would like to place this recording in the spirit of the title of Winterberg's extraordinary song cycle on texts by the Prague poet Franz Werfel.

1950–1952

The time around 1950 was a good one for Hans Winterberg. It represented a first respite after the dramatic odyssey of the war and post-war years. His marriage to the voice student Adelheid Reinhardt (later Ehrengut), whom he presumably met while a lecturer at the Munich Conservatory, finally helped him to obtain a German passport in 1950. Born in Prague in 1901 as an Austrian citizen of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, this was his fifth "change of identity" after gaining Czechoslovakian citizenship in 1918, losing it in 1939 due to the annexation by Nazi Germany of the so-called "rump of Czechoslovakia," regaining a Czechoslovakian passport after his liberation from the Theresienstadt concentration camp in 1945, and emigrating to Bavaria in 1947, which made him a stateless person or an "ethnic German." Winterberg's Bohemian-Jewish family, which had lived in Prague for centuries, had declared their allegiance to the Czech language and the Czech culture in the 1930 census, in contrast to many other German-speaking Jewish families and, of course, the Sudeten-Germans, the majority of whom longed for annexation to the German Reich after 1933. As a result, Winterberg was indeed spared expulsion from Czechoslovakia after the Beneš Decrees came into force. But when he returned to Prague from Theresienstadt in June 1945, he was alone. His wife Maria Maschat, who was not Jewish, and their daughter Ruth had been forced to leave Czechoslovakia. Virtually his entire family, his Jewish former friends and colleagues had been murdered, and all his non-Jewish fellow students from the master classes of Alexander Zemlinsky, Fidelio F. Finke, and Alois Hába had resettled in Germany. Acting out of necessity, hardly out of an inner desire, he emigrated to Munich in 1947, before the communist coup d'état, to be near his wife, whom he had been forced to divorce in 1944, and his daughter, but above all also near a number of musicians who were to support him in building an initially very promising career.

His most important champion was undoubtedly Fritz Rieger, a fellow student in Prague. From 1947, Rieger held the position of chief musical director of the National Orchestra in Mannheim, where in 1949 he premiered Winterberg's First Symphony, which had already been completed before the war. That same year, Rieger succeeded Hans Rosbaud as music director of the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra. Already in his second season, he conducted the world premiere of Winterberg's First Piano Concerto (13/11/1950), followed by the world premiere of the Second Piano Concerto (29/01/1952), and – on the day of his appointment as General Music Director of the City of Munich – the world premiere of Winterberg's Suite for String Orchestra (12/02/1952). In the 1952/53 season, he ceded the reins to the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra's chief conductor Jan Koetsier for the premiere of Winterberg's Second Symphony (19/12/952). During this time, Winterberg not only established contacts with musicians of the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra, but also with those of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra. Thus, on 15 February 1951, the Koeckert Quartet, the legendary formation under the concertmaster of the Radio Symphony Orchestra, played the world premiere of Winterberg's Second String Quartet from the war year 1942. Winterberg thus experienced in close succession prominent performances of works already composed in Prague as well as newly composed works. Inspired by euphoric audience reactions ("The premiere of Hans Winterberg's Piano Concerto elicited a tumultuous demand for a da capo." Süddeutsche Zeitung, 17/11/1950) and excellent reviews, he wrote marvelous chamber music during this period, such as the Suite for viola and piano, the Cello Sonata (both EDA 51), the Concertino for trumpet, horn, trombone, timpani, and piano, and the Rhapsody for trombone and piano.

The Trio, written in 1950 for the variable instrumentation of clarinet or violin, cello, and piano, was premiered on 18 January 1952 in Munich's Amerika-Haus by the trio of Munich pianist Rosina Walter with dedicated chamber music colleagues Ludwig Baier (violin) and Kurt Engert (cello). At this time, Engert was principal cellist of the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra, Ludwig Baier a member of the violin section of the same orchestra as well as second violinist of the Sonnleitner Quartet, the string quartet of the Philharmonic's concertmaster, and the ensemble that was to premiere Winterberg's Third String Quartet in 1971. Better and more respected musicians were hard to find in Munich at that time.

A further performance by the Walter Trio is not documented, but the Magda Rusy Trio played it on a concert tour in 1954/55. Rusy, born in Karlsbad in 1907, was highly respected in Munich and lived in Dießen am Ammersee, not far from Winterberg, who had resided in Riederau since 1948. As a Sudeten-German, she was obviously associated with the expellee associations – the Munich concert of the tour, which began in Maribor in August 1954 and also led the musicians to Belgrade, Vienna, Graz, and Zagreb, took place on 15 January 1955 in the hall on Sophienstraße. The event was organized by the Bavarian regional group of the Artists' Guild of the Association of Expelled Creative Artists, which was founded in Esslingen in 1948. Presented under the motto "Music from Bohemia" were trios by Fidelio F. Finke, Heinrich Simbriger, Hans Winterberg, and Antonín Dvorák. An extremely revealing program grouping. Here we see Winterberg not only in the context of one of the forefathers of the Bohemian musical tradition, in which he saw himself rooted. He and Fritz Rieger had studied with Fidelio F. Finke, rector of the German Academy of Music in Prague between 1927 and 1945, as had also Heinrich Simbriger, who was to become increasingly important for Winterberg in the following years and who, from 1966, built up at the Artists' Guild in Esslingen the music archive that was dedicated to the works of German composers in the former "German eastern territories." We will come back to him in connection with the Sudeten Suite.

Winterberg's position in the context of contemporary music in Germany is clearly visible from the reviews in the Munich press at this time. Beside the mention of his origins and his teachers, we time and again encounter the stereotyped emphasis on "non-German" attributes. This could well have been intended to be positive, even if his music at the same time also served to polemicize against the "Darmstadt/Donaueschingen avant-garde" that was establishing itself in the 1950s. For example, in the review of the premiere of the Suite for String Orchestra in February 1952, a month after the premiere of the Piano Trio: "His descent from a land of rhythm, namely Bohemia, protects him from intellectualistic adventures, in which I also see a reason why Rieger is interested in him" (Süddeutsche Zeitung, 14/02/1952). A snide remark aimed at the "intellectualist programs" of Rieger's predecessor Rosbaud. Seemingly favorable, but full of resentments, the Süddeutsche Zeitung then appraised the Trio after the Munich performance in January 1955 as "an impressionistic-Slavophile, formally carefree but colorfully sensitive and melismatically delicate filigree work." And elaborates: "Winterberg's opus, finding its way from vagabonding, contourless impressions to the Slavic mainland of rhythmic emphases, represents in itself a small process of development, as if the talented, sensitive author only discovered himself while composing. Yet, I would almost like to believe that this stylistically vacillating self has its place among Debussy's successors." This is highly tendentious in all its mannerism but contains a correct observation: The "development process" from a seemingly free-associative, rhapsodic, tonally picturesque texture to a focus on rhythmically profiled, energetic dance processes is indeed characteristic of Winterberg and is what accounts for the charm of many of his works.

With a playing time of almost seventeen minutes and a four-movement structure, the Trio is one of Winterberg's weightier chamber music works in comparison to his concisely conceived three-movement suites. It captivates with its formal perfection, its enormous wealth of contrasts on a formal, "narrative," and emotional level, with subtle humor and a good dose of irony that has to be revealed interpretatively. It is an incredible arc of tension that is drawn here, from the melancholy, pastoral opening movement with its echoes of Mahler's "Changing of the Guard in Summer" in the secondary theme through the pale colors of the Andante sostenuto to the cheerfully buoyant "courtly" Tempo di Minuetto, which is swept away by a very pagan Allegro barbaro that pays its respects to Bartók and in which one is inclined to see the origins of ragtime and boogie-woogie in Bohemian folklore.

Conspicuous is that the "impressionistic" as well as the "Slavophile" moments play a lesser role in the Second Trumpet Suite of September 1952, with which Winterberg concluded the series of chamber music works from the early 1950s. It is as if, in response to the reviews that accompanied his arrival in Munich's musical life, he wanted to conceal his obvious status as a musical outsider and prove rather that he belonged to the German tradition by emphasizing the "new objective" stylistic characteristics à la Hindemith and Weill. Owing to a lack of sources, we can only speculate about the background of the Second Trumpet Suite's genesis. It may have been written at the suggestion of Munich trumpeter Willy Brem, who played Winterberg's First Trumpet Suite, which was composed in Prague in the fall of 1945, with great success at Amerika-Haus in Munich on 2 March 1950.1 Performances during Winterberg's lifetime are not documented.

1942–1944

Only after the fall of the Berlin Wall did the international music world, through the incipient preoccupation in the 1990s with the so-called "Theresienstadt composers," become aware of the fate of Czechoslovakia's Jewish musical elite, who with only a few exceptions fell victim to the Shoah. Hans Winterberg – who, like Hans Krása, had studied piano with Theresia Wallerstein (the sister of director Lothar Wallerstein) and from 1937 completed further studies (together with the eighteen-year-younger Gideon Klein) with the quarter- and sixth-tone apostle Alois Hába – was not one of them, and yet again he was. The reason why he was not deported to Theresienstadt already in 1942 can be explained by the fact that he was initially protected by his "mixed marriage" to a Sudeten-German and because of their daughter. What is certain is that he was separated from his family that year and had to move into a so-called Jews' house. As can be seen from the files of the Bavarian State Compensation Office, he was compelled to perform forced labor starting in 1941. The marriage was dissolved in December 1944 “in accordance with the "Reich's Marriage Law," and from that moment on, there was really no possibility for him to escape the German extermination machinery. Winterberg survived the period between the German annexation of Austria, being banned from his profession, and his deportation to Theresienstadt on 25 January 1945, apparently under conditions that enabled him to acquire music paper and to compose. The look of his music handwriting bears testimony to the condition he was in. Between 1942 and 1945, he composed the 2nd String Quartet, two Suites – one for violin and piano, the other for clarinet and piano – and the Second Symphony, the last movement of which was completed only after the war – as "Survival Symphony," one of the most poignant testimonies of spiritual resistance to the Nazi terror and a counterpart to the "Non-Survival Symphony" of his comrade-in-suffering Pavel Haas.

Both suites are distinguished by their aphoristic brevity and their extremely idiomatic instrumental parts: Expressive melos, virtuoso arpeggios and double stops give the violin opportunity to demonstrate technical mastery, just as the clarinet can prove its agility with fast runs, breakneck leaps over several octaves, and special effects such as flutter tonguing and glissandos. For Winterberg, 1942 marked the beginning of a period of complete uncertainty. His mother and Therese Wallerstein were deported to Theresienstadt, from there to the Maly Trostinets extermination camp south of Minsk, where they were murdered. Although Winterberg learned the exact details of their tragic end only years after the war. However, personal suffering or consternation is expressed in the suites only in a very sublimated form. Most of all in the first two melancholy movements of the violin suite. Distinctive then is the impetus of the last movement with its carved-in-stone dotted and syncopated piano chords that sweep away all tendencies towards resignation with wild defiance. More than the Violin Suite, the Clarinet Suite seems to reflect the state of an individual who has fallen out of all "logical" space and time continuities. The piano ostinatos that dominate the entire second half of the first movement appear to be frozen in time, with the clarinet levitating rhythmically above them, reflecting upon being. The second movement is titled "Interlude." The slowly arpeggiated dissonant layers of chords bring to mind the towers of chords in Berg's third Altenberg lied: "Leben und Traum vom Leben, plötzlich ist alles aus" (Life and the dream of life, suddenly everything is over). The "Interlude" is not the bridge to a next movement, like the "Intermezzo" in Brahms's Third Piano Sonata, but rather is followed immediately by the "Postlude," as if the music that should logically follow was no longer there. The two suites are prime examples of Winterberg's mastery of polyrhythmic and polymetric techniques, perfected in the 1930s, with which he achieved enchantingly, excitingly beautiful effects. On the title page of the manuscript of the Clarinet Suite, Winterberg wrote "Gall, Filharmoniker," referring to the legendary Rudolf Gall, principal clarinetist of the Munich Philharmonic and a member of the Munich Wind Quintet. Winterberg must have offered the work to him. It has not yet been possible to establish whether a performance by Gall actually came to pass.

1937

After completing his studies in composition and conducting at the German Academy in Prague, Winterberg worked for a time as a répétiteur and conductor at the theaters in Brno and Gablonz before taking up residence again in Prague as a freelance composer and theory teacher. In the mid-1930s, he started a family with the renowned pianist and composer Maria Maschat, who was born in Teplitz in 1906. In 1935, their daughter Ruth was born. Material security was provided by a monthly appanage from his father's flourishing textile factory. This period was enormously prolific in terms of composition: it saw the creation of the First Symphony, the 1st String Quartet, the Violin Sonata (both EDA 51), the First Piano Sonata (EDA 54) – Winterberg began to make use of the great traditional forms in a very individual way. But with the Quintet for violin, 2 clarinets, horn, and piano and the song cycle Dort und Hier ("There and Here") for soprano and piano trio he also experimented with unconventional instrumentations and formats. In 1935/36, he associated himself with Viktor Ullmann, Walter Süßkind, Friederike Schwarz, Wilhelm M. Wesely, and Karl Maria Pisarowitz to form a loosely connected group of young German-Bohemian composers. In a jointly organized concert in Prague's Urania in December 1935, he presented his Three Songs on Poems by Franz Werfel. The composer himself accompanied the soprano Marta Tamara Kolmanová (murdered in Auschwitz in 1944), an ensemble member of the Prague Opera. Werfel was Winterberg's preferred poet. From the preserved lied compositions of these years, it is obvious that he initially worked toward the genre of the art song with songs based on his own texts and only dared to tackle Werfel's poetry when he felt he was up to the challenge. The cycle Dort und Hier is the conclusion and culmination of Winterberg's preoccupation with Werfel, and indeed one of the rare works with this scoring. Whether Winterberg knew Werfel or Prague's other important German-language writers personally is not known. Although he lived practically around the corner from Café Arco in the Hybernergasse, not far from the main railway station, which Kisch, Brod, Kafka, Werfel, Rilke, and all the others frequented, by the mid-1930s it had already lost its importance as a meeting place for Prague's literary and artistic German-speaking Jewish elite.

Dort und Hier, started in 1936 and completed in January 1937, brings together four poems by Werfel from different periods and from different publications. However, all four are found in a volume curated by the poet himself and published in 1935, which Winterberg may have had at his disposal. The selection of texts is disconcerting at first owing to their apparent disparity, and baffling because of Werfel's unconventional approach to universal themes. In the Marian scene of the first song – a paraphrase of the "Flight into Egypt" set in a bleak winter landscape – Werfel addresses the existentialist experience of helplessness. The second and third songs deal with the passage from this life to the hereafter from a religious and erotic perspective. One is naively touching, pertly ironic, and a touch heretical. The other, which gave the cycle its name, is ecstatic. The falling of snow, in turn, serves Werfel as a metaphor for the apparent chaos of the world, behind which however a divine order reigns, and for the idea that with death, man returns from his individuality to the great context of creation. Winterberg deftly uses the thematic starting point in the first song ("wohl besser wärs, es würde schnein" / "it would probably be better if it snowed") for a cyclical bracket to the last. Werfel's ironic-expressionistic language, rich in powerfully pictorial neologisms, inspired him to gripping, nuanced, and colorful music, full of subtle realizations of musical imagery: the winter torpor of nature in the first song, for example, through pale, static sounds, or the cawing of the crows by "scratchy" violin volutes played con sordino. In the last song, the whirling of the snowflakes is a welcome opportunity for him to demonstrate breathtaking polyrhythmic feats of incomparable effect, the likes of which we only see again in late Ligeti: held together only by a common pulse, the individual voices (including the two pianistic hands) drift along independently, each following its own metric system of order – an evident realization of the idea of unity in diversity.

1963

Winterberg's successes of his initial period in Munich were not lasting. The number of important performances and radio broadcasts dwindled increasingly over the years. With Rieger's departure from Munich, the door to the Philharmonic Orchestra closed; Jan Koetsier still undertook the premiere of the Third Piano Concerto in 1970, but, as the second man alongside Jochum, he did not perform a single work by Winterberg with the Bavarian Radio Orchestra. And Winterberg's compatriot Rafael Kubelik, who succeeded Jochum in 1961, was not interested in Winterberg’s music. Connections to other orchestras such as the Graunke Symphony Orchestra in Munich, the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra, and the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra remained sporadic. Winterberg existed in constant material need. He barely earned a living wage from the pitiful salary he earned as a freelancer for Bavarian Radio and from the few hours he put in at the conservatory. He had to fight for years with the help of a lawyer to obtain compensation for the physical and professional deprivations he suffered during the Nazi occupation of Prague. That moderately avant-garde music of the kind he composed was ignored by a young generation of composers and editors was his second bitter experience in life. Already in 1956, he wrote to Heinrich Simbriger, who was active in the Esslingen Artists' Guild, that he had to interrupt work on his current composition because he did not have any money for music paper. As far as Winterberg's recognition as a composer was concerned, Simbriger and the Artists' Guild became a lifeline, also financially. This came at a price: increasing absorption by the Association of Expelled Sudeten Germans, which was further encouraged by Winterberg's (fourth) marriage in 1968 to the painter and poet Luise Marie Pfeifer, who was born in Tetschen-Bodenbach (now Děčín). The unsettling "Sudeten-German" complications that eventually arose with his estate can be read about elsewhere.2

The Sudeten Suite, composed in 1963/64, must be viewed against this background. The circumstances of its creation and its premiere illustrate the whole perfidiousness and bitter irony of Winterberg's post-war fate. On 31 May 1963, Winterberg was awarded – through Simbriger's mediation – the Culture Prize of the Sudeten-German Territorial Association by Federal Minister Hans Christoph Seebohm and Federal Director of Cultural Affairs Viktor Aschenbrenner. Seebohm, German Minister of Transportation since the founding of the Federal Republic, had been spokesman for the Territorial Association since 1956 and belonged to its revisionist block. After the Munich Agreement and the annexation of the so-called Sudetenland by the German Reich in 1938, he was involved in the Aryanization of Jewish businesses. Aschenbrenner, councilor in the Hessian state government and chairman of the cultural committee of the Federation of Expellees, had joined Konrad Henlein's Sudeten-German Party in 1937 and during the Nazi era held a leading position as head of the district central office of the Nazi organization "Strength through Joy." Winterberg was thus honored by the people who were largely responsible for the end of the Czechoslovak Republic and the expulsion and extermination of the Jewish population.

The Sudeten Suite was composed in late 1963, early 1964, i.e., after the awarding of the Culture Prize and before Winterberg was presented a second "Sudeten-German" prize, the recognition award of the 1964 Johann Wenzel Stamitz Prize (the main prize that year went to Günter Bialas and Heinz Tiessen). In comparison to Hans Winterberg's rhythmically and harmonically highly complex works of the 1960s, it undoubtedly seemed like a foreign body with its post-impressionistic, easily comprehensible tonal language. It is obvious that the work was intended as a musical salutation to Simbriger and the officers of the Artists' Guild. It was then also premiered by the Louegk Trio (consisting of Günter Louegk, piano, Gerhard Seitz and Walter Nothas, concertmaster and solo cellist, respectively, of the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra) in a concert organized by the Adalbert Stifter Society on Bavarian Radio on 15 June 1966. Among the guests of honor: Hans-Christoph Seebohm. Did Winterberg, a Jew from Prague, want to make a musical avowal to Sudeten-Germanism with this work? Hardly. Significantly, it does not bear the title Sudeten-German Suite. The three movements do not allude to German culture in the former "eastern German territories," but rather to scenic attractions, to demarcation points especially of the Czechoslovak territory on the border to Poland in the north (Schneekoppe, Elbquellen) and to Austria and Germany, the so-called border triangle, in the south (Plöckenstein). These are places where Winterberg went wandering, in times when his Czech-German-Jewish identity was viable as a harmonious triad. Identitarian madness transformed this triad into a dissonance with which he had to juggle since his persecution as a Jew and then as an exile in West Germany. It is program music in the best sense in the tradition of Smetana's cycle My Fatherland (Má Vlast), a composed recollection of formative landscapes that for Winterberg became inaccessible behind the Iron Curtain after his move to Munich. The Sudeten-German milieu could see this as an "avowal," for him it was an immersion in the lost paradise of his childhood.

Frank Harders-Wuthenow

(engl. translation: Howard Weiner)

______________________

1 See booklet text to EDA 51 and the commentary about the work by Michael Haas at www.boosey.com/Winterberg.2 See Peter Kreitmeir's website and Michael Haas' blog.