III: Bolko von Hochberg – Piano Quartet in B-flat major op. 37

Please select a title to play

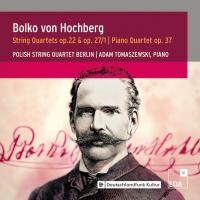

I: Bolko von Hochberg – String Quartet in E-flat major op. 22

I: Bolko von Hochberg – String Quartet in E-flat major op. 22I: Bolko von Hochberg – String Quartet in E-flat major op. 22

01 Allegro energico e maestoso

I: Bolko von Hochberg – String Quartet in E-flat major op. 22

02 Scherzo – Allegro

I: Bolko von Hochberg – String Quartet in E-flat major op. 22

03 Non troppo lento

I: Bolko von Hochberg – String Quartet in E-flat major op. 22

04 Tema con Variazioni

II: Bolko von Hochberg – String Quartet in D major op. 27,1

05 Allegro moderato

II: Bolko von Hochberg – String Quartet in D major op. 27,1

06 Tema con Variazioni – Andante con moto

II: Bolko von Hochberg – String Quartet in D major op. 27,1

07 Minuetto

II: Bolko von Hochberg – String Quartet in D major op. 27,1

08 Allegro giusto

III: Bolko von Hochberg – Piano Quartet in B-flat major op. 37

09 Allegro fiero

III: Bolko von Hochberg – Piano Quartet in B-flat major op. 37

10 Lento e mesto

III: Bolko von Hochberg – Piano Quartet in B-flat major op. 37

11 Scherzo

III: Bolko von Hochberg – Piano Quartet in B-flat major op. 37

12 Allegro assai

Bolko von Hochberg

From a socio-historical point of view, the nineteenth century represents the period in Western music history in which the middle classes finally replaced the old feudal structures as the main pillar of musical life – a process that took place gradually, so that for a long time a courtly musical life existed alongside that of the civil society: Beethoven, who in later generations became the epitome of the freelance bourgeois musician, received a pension from aristocratic patrons until his death, and Richard Strauss, who no less adeptly combined artistic independence with bourgeois business acumen, spent a good three decades of his conducting career as court music director.

The man to whom Strauss owed his position as court music director in Berlin was a count and the son of a prince, and was never dependent on earning money with his compositions. As director of the Prussian court theaters, he could at that time have been considered the representative in Germany of the courtly music world par excellence. At the same time, he was the founder of one of the most important German music festivals, with which he placed himself in a tradition of decidedly bourgeois musical culture. And in this context, he did not forgo an opportunity to appear in public as a pianist and singer, like an ordinary middle-class musician.

Hans Heinrich XIV Bolko Count von Hochberg stemmed from a Silesian noble family first documented in 1185, which was elevated to a countship of the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1666. Since 1509, Fürstenstein Castle near Waldburg, the largest castle in Silesia, now located in Poland not far from the border with the Czech Republic, came into the family's possession. Bolko von Hochberg was born there on 23 January 1843, the youngest of five children of Count Hans Heinrich X von Hochberg and his wife Ida von Stechow-Kotzen. His father inherited the principality of Pleß in 1847, which was adjunct to his elevation to the rank of prince by the Prussian king. The flourishing mining industry in the Waldenburg black-coal mines brought the family immense wealth. As the younger son, who did not inherit the title of prince, Bolko was destined for a diplomatic career and, after completing the obligatory legal and political science studies in Bonn and Berlin as well as officer training, went to St. Petersburg in 1867 as military attaché of the Prussian legation and later, for a short time, to Florence. Already in 1869, he quit this service, returned to Silesia, married in that same year Princess Eleonore von Schönaich-Carolath, with whom he would have four sons and two daughters, and from then on dedicated himself primarily to his favorite pastime: music. With this decision, the young count was able to follow the tradition of his family, as he was a great-great-grandnephew of Prince Leopold von Anhalt-Köthen, who went down in musical history as Johann Sebastian Bach's greatest patron. In contrast to Leopold, Bolko von Hochberg was not only a performing, but also a creative musician. He had acquired the technical skills for this during his time in Berlin as a student of Friedrich Kiel, Prussia's most respected composition teacher, who later dedicated his two piano trios op. 65 to him.

Hochberg first called attention to himself publically as a composer in 1864, when his Singspiel Claudine von Villa bella was premiered at the Schwerin Court Theater. In order to avoid any possible disapproval of his artistic activities on the part of his peers, he had his works performed and published until 1879 under the pseudonym "J. H. Franz." After that, he confidently appeared only under his real name, which he had already made known in parentheses on the title page of the last "Franz" print, the Symphony no. 1, op. 26.

Hochberg numbered among the most important private patrons of German musical life of his time. He began his sponsorship activities in 1872 within a small circle when he took a string quartet, founded two years earlier by students of Joseph Joachim, under his patronage. Initially active only in the count's apartment in Dresden and at his Castle Rohnstock in Silesia, Ernst Schiever (Violin 1), Hermann Franke (Violin 2), Leonhard Wolff (Viola), and Robert Hausmann (Violoncello) soon went on tours as the Princely Hochberg Quartet. Their triumphs simultaneously promoted their patron, who turned to a much more ambitious project in 1876 after the quartet broke up: under great strain to his own assets, he founded the Silesian Music Festivals, a response to the very successful Lower Rhenish Music Festivals, which had been presented annually since 1818. By 1925, Hochberg had organized a total of nineteen of these festivals, which usually took place every two or three years in Hirschberg in the Giant Mountains, Breslau, or Görlitz. From 1889, Görlitz became the permanent home of the event.

The art-loving count's organizational talent did not go unnoticed at the Prussian court. In 1886, Kaiser Wilhelm I appointed him General Director of the Königliche Schauspiele, with which the responsibility for the court theaters in Berlin, Hanover, Kassel, and Wiesbaden passed into Hochberg's hands. The new director proved to be a social-minded employer, for under his leadership the first contracts were concluded that conceded the theater personnel a retirement pension. As sometime president of the German Theatrical Association, he strove to establish this as a general practice in the theater world. Hochberg's personal profile soon made its mark in the repertoire in the form of an intensified cultivation of the music of Wagner, which was reflected in particular in the first performance of the Ring cycle at the Berlin Court Opera "Unter den Linden." It was only at this point in time that Wagner entered the permanent repertoire of the most prestigious Prussian theater. Young conductors such as Karl Muck, Felix Weingartner, and Richard Strauss, whom Hochberg appointed Court Music Director in 1898, provided for performances of the highest level. In the choice of singers, the director demonstrated no less skill. When planning his season's repertoire schedule, Hochberg had to take into consideration the tastes of the kaiser – Wilhelm II reigned from 1888 – as well as those of the bourgeois audience. It is therefore not surprising that under his directorship a large portion of the presented repertoire consisted of light and representation pieces typical of the time. Nevertheless, he occasionally risked staging novelties that struck out on new paths beyond the existing conventions. Thus, in 1893, Gerhart Hauptmann's dream poem Hanneles Himmelfahrt was staged for the first time in Berlin's Schauspielhaus, an event received with disconcertment at court. Hochberg took leave of the theater in 1902. As a consequence of the Berlin premiere of Richard Strauss's Feuersnot, a circle around Prince Philipp of Eulenburg had denounced him to the emperor for the staging of the "indecent" work. At the same time, defamatory rumors were spread about Hochberg's influential "artistic secretary," the former bookseller Henry Georg Pierson, who took his own life shortly thereafter. In 1903, Eulenburg's protégé Georg von Hülsen-Haeseler succeeded Hochberg.

Hochberg returned to Rohnstock Castle and from then on dedicated himself entirely to the Silesian Music Festivals. Having financed, together with the Province of Silesia and the provincial estates of Upper Lusatia, the conversion of a former exhibition building into a concert hall on the occasion of the first Görlitz Festival in 1878, after 1900 he substantially furthered the construction of the new Görlitz Civic Center, which was inaugurated in 1910 by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra under Karl Muck. That same year, Hochberg was awarded the honorary citizenship of the city of Görlitz. After the festivals had not taken place for over a decade as a result of the First World War and the economically difficult postwar period, the eighty-two-year-old Hochberg was able to resurrected them in 1925. He died a year later, on 1 December 1926, in the spa town of Salzbrunn not far from Fürstenstein Castle.

Bolko von Hochberg was an excellent pianist and singer and, after having given up his pseudonym as a composer and started publishing his works under his real name, he also dared to present himself before the public as a performing musician. With the Silesian Music Festivals, he also created a platform for himself to make music in front of an audience as a piano accompanist or singer. For example, at the fourth Music Festival in 1880, he sang the bass parts in excerpts from Beethoven's Fidelio and Verdi's Rigoletto. Above all, however, he performed his own songs. His instrumental works could also be heard regularly within the framework of the festivals.

Hochberg's catalog of works extends to opus number 42 and includes a total of around ninety individual pieces. With the singspiel Claudine von Villa bella and the romantic opera Der Währwolf (first version under the title Die Falkensteiner), these include two major stage works. Small-scale vocal music is represented above all by numerous songs and ensemble pieces with piano accompaniment, which formed the main focus of his early creative period. For orchestra, he wrote three symphonies and a piano concerto that was particularly praised by critics. This op. 42, published in 1906, is at the same time his last known composition. In the area of chamber music, Count Hochberg wrote three string quartets, two piano trios, and a piano quartet.

The String Quartet in E-flat major, op. 22, Hochberg's first multi-movement instrumental work, was published in 1874 by Johann André (cf. EDA 50)1 in Offenbach. It is safe to assume that it owes its creation to the composer's interaction with the string quartet that Gerhart Hauptmann refered to in his memoirs, Das Abenteuer meiner Jugend, as "the famous Hochberg violinists." Whether this was also the case with the following D major quartet is unclear. It was first published by Bote & Bock in Berlin in 1894 together with Hochberg's Third String Quartet in A Minor as op. 27, but is probably much older, since the composer's song collections, designated ops. 30, 31, and 32, had already appeared in 1886. By contrast, the Piano Quartet in B-flat major, op. 37, is a late work. It was released in 1908 by Ernst Eulenburg in Leipzig and represents the composer's last publication.

If Hochberg's activity as a general director can fundamentally be characterized as the work of a conservative who carried forward the inherited traditional without becoming rigid in its conventions, who left his mark on the organization by making the necessary innovations, and showed himself quite capable of taking risks, his compositional work presents a very similar picture. The composer's spiritual home was the First Viennese School along with the tradition of the Berlin academics, as embodied by his teacher Friedrich Kiel, committed to its legacy. Thus, throughout his life, he also never questioned the formal language of the classical period. His sonatas are in four movements; his variations orient themselves strictly on the structure of the theme, just like in Brahms; the chromaticism, which he used so freely, is always within the framework of classical harmony and counterpoint – not a trace of Wagner, whom he promoted so decisively in the theater! But within the classicistic framework, Hochberg ruled sovereignly. He avoided the conventional tonic-dominant contrast in the first movements of all three works recorded here: thus, the second part of the exposition in the E-flat-Major String Quartet is in A-flat major, in the D-Major String Quartet (to be played pizzicato) in F-sharp minor. In the Piano Quartet, where with the main key of B-flat minor a subsidiary theme in D-flat major could actually be expected, the corresponding idea appears however in the dominant key of F major and then wanders a fifth higher to C major. Hochberg gives expression to his skill in contrapuntal composition through the frequent use of imitative voice leading. Fugati are also regularly found in his works: the finale of the String Quartet op. 27 no. 1 is fugal over long stretches; in the corresponding movement of the Piano Quartet, a fugato, which is not based on the upper voice of the main theme but on its bass, surprisingly breaks forth in the development; the middle section of the C-minor Rondo, which substitutes for the slow movement in the String Quartet op. 22 and in whose main theme a characteristic augmented second stands out, is likewise written as a fugue. Hochberg displays good-natured humor when, in the second trio of the minuet of op. 27, no. 1, he has the folk song Lieber Nachbar, ach borgt mir doch Eure Latern appear first in minor and only afterwards in the original major key. At the end of the E-flat-Major String Quartet, there is suddenly a calm coda after the light-footed last variation seems to announce an exuberant conclusion. In the finale of the Piano Quartet, the previously so proud subsidiary theme appears in the recapitulation only as a shadow of its former self – the composer, who created a work here in which all the movements are in minor keys, also understond the effect of tragic surprises.

As a creative artist, Bolko von Hochberg may not have significantly influenced the course of music history, but his compositions were well received by connoisseurs and enthusiasts during his lifetime and beyond. In his guides for string-quartet (1927) and piano-quartet players (1937), Wilhelm Altmann could not resist the temptation to be a reminiscence hunter, but he admired the "purity of the genuine quartet-like writing" of the string quartets and warmly recommended the piano quartet for public performance. Already in 1900, Albert Tottmann had spoken of Hochberg's "well-formed, mature, and interesting" works in his guide to violin instruction. And even thirty years after the composer's death, Franz-Jochen Machatius, in his encyclopaedia article for Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, concisely summed up the essence of Hochberg's music when he spoke of its "felicitous noblesse."

Norbert Florian Schuck

English translation: Howard Weiner

______________________

1 EDA 50 First recordings of chamber music works by Johann Anton André with the Polish String Quartet Berlin.