V: Gustav Bumcke – Sonata Bb minor op. 68

Please select a title to play

I: Edmund von Borck – Introduction and Capriccio op. 11 (1934)

I: Edmund von Borck – Introduction and Capriccio op. 11 (1934)I: Edmund von Borck – Introduction and Capriccio op. 11 (1934)

1 Introduction and Capriccio

II: Paul Dessau – Suite (1935)

2 Petite Ouverture

II: Paul Dessau – Suite (1935)

4 Serenade

III: Berhard Heiden – Sonata (1937)

5 Allegro

III: Berhard Heiden – Sonata (1937)

6 Vivace

III: Berhard Heiden – Sonata (1937)

7 Adagio – Presto

IV: Erwin Dressel – Bagatelles (1938)

8 Elegie

IV: Erwin Dressel – Bagatelles (1938)

9 Scherzo

IV: Erwin Dressel – Bagatelles (1938)

10 Aria

IV: Erwin Dressel – Bagatelles (1938)

11 Gigue

V: Gustav Bumcke – Sonata Bb minor op. 68

12 Allegro appassionato

V: Gustav Bumcke – Sonata Bb minor op. 68

13 Sostenuto

V: Gustav Bumcke – Sonata Bb minor op. 68

14 Allegro molto

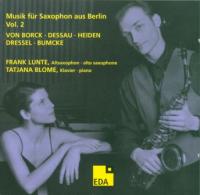

In Berlin of the 1930s an attempt was undertaken to come to terms with the saxophone as a classical instrument. Broken off because of repression and war, it found its continuation only in the 1980s. This CD is the second of a three-part series that presents compositions for the chamber music formation of alto saxophone and piano. The series begins with 1930 and continues to the compositional events of the beginning of the twenty-first century. Vol. 1 (EDA 21) and vol. 2 cover the 1930s (1930-32 and 1934-38, respectively), with vol. 3 (EDA 29) devoted to music written since 1982, whereby the most recent compositions are dedicated to the Duo Frank Lunte and Tatjana Blome.

"Only now does the saxophone begin its real triumphant advance, in fact also in modern, serious opera and concert music. One only slowly dares to go near this strange instrument with its highly individual timbre. .... It is not difficult to recognize the importance that the use of one or more saxophones can attain in the future in serious art music." (Edmund von Borck: Bläser heraus!, in: Allgemeine Musikzeitung Berlin, 12 February 1932).

In the 1930s, Edmund von Borck was considered one of the most brilliant young German composers. Born in 1906 in Breslau, Silesia, he received his training in composition, piano, and conducting in his hometown and in Berlin. He was subsequently active in Frankfurt as conductor at the opera house, but soon returned to Berlin and taught at the "Konservatorium der Reichshauptstadt" ["Conservatory of the Imperial Capital"]. As a conductor he worked with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and Amsterdam's Concertgebouw Orchestra. His Concerto for Saxophone and Orchestra, op. 6, was the first solo concerto for this instrument; it was inspired by the legendary saxophone virtuoso Sigurd Raschèr. The Concerto was premiered in 1932 with great success, by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra under Borck's direction, in Hannover at the German Musicians' Association Convention.

The work recorded here, Introduction and Capriccio, op. 11, was written two years later and is exemplary for Borck's compositional style, which was described by Hans Gresser as follows: "The rhythmic impetus, which practically never breaks off, is based ... on the mutual urging on of the various voices. ... The predilection, also to be observed in Borck, for a certain quartal harmony is typical for a time in which composers moved away from the overabundant chromaticism of the Tristan succession, could not return to the 'classical' harmony, but for the most part were also not inclined toward atonality and dodecaphony, but in which all sought new ways out of the bonds of major-minor tonality" (Hans Gresser: Edmund von Borck – ein Fragment, Laumann Verlag, Dülmen 1989). The Introduction, whose restless sixteenth-note triples are built over a dominating quartal foundation, is definitely atonal. The excitement culminates in a double trill that suddenly leads into the Capriccio. The 6/8 meter, suggesting dance-like motion, is led ad absurdum by the "false" accents on the (normally) unaccented beats. Frequent tempo changes underscore the vital expressionism that characterizes Borck's complete œuvre.

As a composer, Borck was quickly able to notch up successes, which however were in no way due to a particular patronage on the part of the ruling regime. To be sure, he was able to work unhindered in spite of his nonconformist musical language, yet the fact that Borck was called up for military service already in 1940 points, on the other hand, to the systematic prevention of a career that in all probability would have been unwelcome to the regime. Since the German troops in allied Italy were initially only intended to demonstrate presence, and not involved in fighting, Borck was occasionally able to take a leave of absence from his base there. Thus it was possible for him to accompany the premiere of his opera Napoleon, which took place in Gera in 1942 – with triumphal success. It was to be his last: Edmund von Borck fell, at the age of thirty-eight, on 15 February 1944 at Nettuno, Italy.

Paul Dessau was born in 1894 into a family with a musical tradition; his grandfather and great-grandfather were cantors of the German-Jewish congregation in Hamburg. Dessau initially studied violin, but later decided on a career as conductor. In 1912-13 he received his first engagement as rehearsal pianist at the Hamburg Municipal Theater. After military service in 1915-18, he assumed in 1919 a position as conductor at the Cologne Opera under Otto Klemperer, with whom he established a lifelong friendship. In 1923 followed the position as principal conductor in Mainz, and two years later the same position at the Berlin Municipal Opera under Bruno Walter, which he held until 1927. In 1928 – still during the era of the silent movie – Dessau was engaged by Berlin's Alhambra Cinema, initially as a violinist, then also as conductor and composer. In this movie theater he established novel cultural programs; Paul Hindemith, Arthur Schnabel, Kurt Weill, and Otto Klemperer, among others, participated in his "Midnight Concerts." Shortly after Hitler's seizure of power in 1933, Dessau fled from Germany and went to Paris. There he met René Leibowitz and began to occupy himself with twelve-tone technique. Dessau was always anxious to master various compositional techniques, yet never an advocate of any one trend. "Music is not dependent on the means, not on the glissandos, nor on the pizzicatos, nor on the 'below the bridge', not on the 'under the bridge and into the vest pocket, and remove the mouthpiece and blow into it'. One can do that, certainly – the main thing, however, is that the music is good. New means are not a guarantee for good music. There is no guarantee for good music as good music" (from: Aus Gesprächen mit Paul Dessau [From Conversations with Paul Dessau], VEB Deutscher Verlag für Neue Musik, Leipzig 1974).

Dessau wrote the three-movement Suite for Alto Saxophone and Piano in 1935 in Paris, before coming into contact with Leibowitz and dodecophony. Little is known about its history. The second movement carries a friendly dedication to Sigurd Raschèr. The outer movements were probably composed later that same year. In the Petite Ouverture an ostinato accompaniment figure in the piano continually drives forward the enervating saxophone melody. The B section only seems to relieve the tension; the recapitulation is limited to a short reminiscence, then breaks off abruptly. The transition to the Air already breathes its spirit – melancholy and rapture spread out. The third movement, Serenade, develops all the more exuberantly; rich in embellishments and with the sighing "krekhtsn" typical of Yiddish music, it shows Dessau's occupation with his Jewish origins. Whereas Dessau employed the saxophone in several orchestral works written around the time of the Suite, his chamber music oeuvre contains only the present work for this instrument.

With his exile Dessau began to take a political stand, which was increasingly reflected in his works in an artistic-aesthetic manner. The most famous example is the song Die Thälmannkolonne [The Thälmann Crew], which was also written in France. At the outbreak of war in 1939 he went to the USA, where an intensive collaboration with Bertold Brecht was established. In 1949 he returned to Germany and decided to settle, as a convinced Communist, in the Soviet zone. Because of his critical solidarity with the ruling Communist party, his works were viewed with suspicion by the national cultural authorities of the German Democratic Republic. He nevertheless felt himself morally, politically, and artistically obliged to his country. Paul Dessau died on 28 June 1979 in Zeuthen near Berlin.

Bernhard Heiden (originally Levi) was born into a musical family in 1910 in Frankfurt. Already early on he received artistic impulses from his mother; frequent domestic music-making accompanied his childhood. At the age of five he received his first piano lessons, several years later also instruction on violin and clarinet. The direction of a Frankfurt school orchestra, with which he had been entrusted, was decisive for his further musical development. He also met Paul Hindemith, still living in Frankfurt at this time, who was to be his composition teacher from 1929 to 1933 at the Berlin College of Music. Hindemith took a very critical attitude toward his new pupil and his works – yet Heiden continued his studies with Hindemith, and later always referred to him as his most important teacher and mentor. In the last year of his studies he won – almost like a reward for his tenacity – the coveted Mendelssohn Prize for Composition. Because of his Jewish origins, he emigrated two years later with his parents to the USA, settling at first in Detroit where he quickly integrated himself in musical life, working as a composer, arranger, pianist, harpsichordist, and organist. He also conducted the Detroit Chamber Orchestra and taught at the Art Center Music School from 1935 to 1943.

Heiden had become acquainted with the new, "classical" treatment of the saxophone in the orchestral context of Ravel's Bolero, Mussorgsky/Ravel's Pictures at an Exhibition, and Hindemith's Neues vom Tage already in Berlin. In 1933 Hindemith had written a Konzertstück for Two Alto Saxophones which provided for lively debate in the circle of his pupils. Yet it was to take several years before Heiden was to decide to compose something for the saxophone. It was the acquaintance with the Detroit saxophonist Larry Teal that led him to write the Sonata for Alto Saxophone and Piano in 1937. Together they played the work for Hindemith, who happened to be visiting in the city; as a result, Hindemith granted his former pupil the long yearned-for acknowledgement, and also arranged for the Sonata's publication by Schott. To Heiden's surprise, Sigurd Raschèr recorded the Sonata in 1945, although Raschèr originally had qualms about the range. "I showed him my Sonata, and he said that the whole thing was too low – the whole thing was an octave too low." (Bernhard Heiden, tape-recorded interview with Thomas Walsh, 12 February 1996, Bloomington, Indiana) Through publication and recordings, the work has become one of the most frequently played pieces for saxophone and piano in America.

In terms of form, the Sonata is neo-classical and strictly polyphonic. The first movement, Allegro, is noteworthy for its rhythmically accentuated style, which is strongly reminiscent of Hindemith's contrapuntal linearity. A more or less Baroque spirit is felt in the second movement, Vivace, whose piano part imitates thoroughbass-like harpsichord playing. The final movement begins with an elegiac Adagio, whose main motif is at first taken up in its original form in the subsequent Presto, before it, as a mere motivic reminiscence, repeatedly calls to a halt the busy chains of sixteenth-notes in both instruments. After a last short adagio section, the tension is vented in a furious coda.

Heiden was naturalized in 1941, and drafted into the American army in 1943 – as Assistant Bandmaster of the 445th Army Service Band. In 1945, after his discharge from military service, he studied music history at the renowned Cornell University. In 1946 he assumed the direction of the composition studio at the Indiana University School of Music, a position he held until his retirement in 1981. Heiden was honored with several renowned composition prizes. He died on 30 April 2000 at Bloomington, Indiana.

Already at an early age Berlin-born Erwin Dressel made a name for himself with opera compositions. At the age of only fourteen he made his debut at the Berlin Municipal Theater with incidental music to Shakespeare's comedy Much Ado about Nothing. Dressel received his musical training in his hometown at the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory. From 1919 he was a composition pupil there of Wilhelm Klatte, transferring in 1924 to the College of Music, where he studied with Paul Juon. In 1926 began the collaboration with the Dresden sculptor and author Arthur Zweiniger, who was to write a number of opera librettos for him. The first joint work, the opera Armer Kolumbus [Poor Columbus], was premiered in 1928 with great success at the Kassel State Theater, upon which the critics predicted a brilliant future for the only just nineteen-year-old composer. Further premieres of his operas, all based on texts by Arthur Zweiniger, followed. From 1927 to 1928 he directed the theatrical incidental music at the Hannover Muncipal Theater, and worked on a freelance basis for the radio until the war.

Dressel's music is distinguished by catchy but not trivial melodies, and opulent yet at the same time not bombastic harmonies. In the Bagatelles, this style comes to the fore especially in the Elegy and in the tranquil middle sections of the Scherzo and the Gigue. The Bagatelles seem more streamlined and calm than the Sonata in E-flat Major, op. 26, written six years earlier (recorded on EDA 21), a piece that carries the exuberance of youthful communicativeness within itself. Dressel wrote three works for saxophone and piano, two of them in the 1930s. Like all his saxophone works (including two solo concertos), the Bagatelles from 1938 are dedicated to Sigurd Raschèr.

After his return from a British prisoner-of-war-camp, he was not able to pick up the thread of his early successes, and was forgotten as a composer. Erwin Dressel lived as a freelance musician in Berlin until his death on 17 December 1972.

The composer and music pedagogue Gustav Bumcke was born in Berlin in 1876, and received his training from Max Bruch and Engelbert Humperdinck, among others. Following his studies, he was initially an opera conductor in Constance, Heilbronn, and Bayreuth for three years. In 1902, during a sojourn in Paris, he met Adolphe-Edouard Sax (1859-1945), the son of the saxophone's inventor Adolphe Sax (1814-1894). Immediately fascinated by the instrument, he returned to Berlin with eight saxophones in all sizes and began to study the instrument in the classical manner, based on his college studies of trumpet and piano. Fascinated by the tonal possibilities, he employed the saxophone that same year in a symphony (presumably op. 15). Parallel to his extensive compositional output for this instrument he also held, from 1924, a lectureship for saxophone at Stern's Conservatory in Berlin – in addition to his part-time lectureships in music theory, harmony, and composition – and established there Germany's first saxophone studio. In the foreword of his saxophone method of 1926, Bumcke lamented how difficult it was for "such a valuable instrument for the music" to find acceptance: "In many cases it had to be replaced in the performances by other instruments, since for the most part good players were lacking. Above all there was a complete lack of understanding in the press and public for my idea to introduce the instrument here in Germany. The value of the saxophone is even today not fully recognized. But the time is not all too distant in which one will appreciate it. ... For the saxophone is above all a noble instrument appropriate for serious music, which can find its true recognition only in symphonic music." (Gustav Bumcke, Saxophonschule [Saxophone Method], Verlag Anton J. Benjamin, Leipzig 1926) Toward the end of the 1920s, Bumcke formed the "First German Saxophone Orchestra" as well as a saxophone quartet in which Sigurd Raschèr also played for a short time. After 1936, Bumcke was not able to continue his teaching activities at the Jewish Stern's Conservatory. In that year the National Socialists renamed it the "Konservatorium der Reichshauptstadt". The new director, Prof. Kittel, wanted to retain Buncke as a teacher, but demanded that he join the Nazi party, which Bumcke steadfastly refused to do.

Bumcke's outstanding work as a pioneer of and trailblazer for the classical saxophone in Berlin finds a high-water mark in the Sonata in B-flat Minor, op. 68, from 1938, a time in which he had already been removed by the Nazis from his position as instructor of the "degenerate" saxophone. The three-movement work, held in the late-Romantic style and corresponding in its form to the traditional sonata, was written under the influence of the composer's shattered life's work. To be sure, Bumcke was able to continue teaching music theory at Berlin's Klindelworth-Scharwenka Conservatory, but his saxophone pupils could only take "conspirative" private lessons. He survived the war without being called up for military service, presumably on account of his advanced age. After the establishment of the German Democratic Republic, he accepted a lectureship in music theory at the German College of Music in East Berlin, which he gave up only in 1955 at the age of nearly eighty. Gustav Bumcke died on 4 July 1963 at Kleinmachnow near Berlin.

With the pioneer of the classical saxophone in Germany, we've come full circle in vols. 1 and 2 of the series Music for Saxophone from Berlin, in which works from the short blossoming of the saxophone in the years 1930–1938 are documented. To follow are compositions from 1982 to 2004, which will form the conclusion of the three-part CD series.

Tatjana Blome and Frank Lunte, September 2003