II: Heinrich von Herzogenberg – Piano Quintet C major op. 17

Please select a title to play

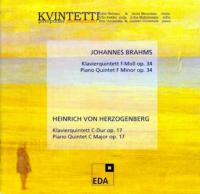

I: Johannes Brahms – Piano Quintet F minor op. 34

I: Johannes Brahms – Piano Quintet F minor op. 34I: Johannes Brahms – Piano Quintet F minor op. 34

1 Allegro non troppo

I: Johannes Brahms – Piano Quintet F minor op. 34

2 Andante, un poco adagio

I: Johannes Brahms – Piano Quintet F minor op. 34

3 Scherzo. Allegro

I: Johannes Brahms – Piano Quintet F minor op. 34

4 Finale. Poco sostenuto – Allegro non troppo – Presto non troppo

II: Heinrich von Herzogenberg – Piano Quintet C major op. 17

5 Allegro moderato, un poco maestoso

II: Heinrich von Herzogenberg – Piano Quintet C major op. 17

6 Adagio

II: Heinrich von Herzogenberg – Piano Quintet C major op. 17

7 Allegro

II: Heinrich von Herzogenberg – Piano Quintet C major op. 17

8 Presto

Now and then musical historiography plays a trick on us. Whoever wanted to be no ticed in the musical world of the second half of the nineteenth century, so it is said, had to be either a "Wagnerian" or a "Brahmsian". This was naturally not the case. The two-party aesthetic system has become the topos of the chroniclers, but only a very few contemporaries made a display of it as unequivocally as musical history would have us believe.

Heinrich von Herzogenberg, for example. Herzogenberg, born in 1843 in Graz as the son of a city treasurer, was destined for a legal career, but then decided to study composition at the Vienna Conservatory, with Otto Dessoff. He won numerous competitions within the school and was considered one of the Conservatory's most promising talents, graduating with honors in 1865. Already two years earlier he had become acquainted with Brahms, primarily because of his connections, less because of his music. For Herzogenberg's model was Wagner. In 1864, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (New Magazine for Music) judged a string quartet by the twenty-one-year-old student to be "even a bit racial, one almost wants to say: neudeutsch ('New German')".

Neudeutsch. When the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik wrote this the term was just five years old, the Ring not yet finished, and Brahms newly arrived in Vienna. Neudeutsch – this stands for the renunciation of tradition, for the break with the old rules. Strictly speaking, it stands for a circle of musicians around Franz Liszt, who coined the term in 1859 at the "ersten Tonkünstlerversammlung" (First Musicians' Congress) in Leipzig. And together with the circle, it stands for the subversive aesthetics of its members, occasionally also for ad hominem attacks of individuals against the old, passé, reactionary music.

As little as all this has to do with music, the provocation was all the more effective. Already in 1860, Brahms, at the recommendation of Joseph Joachim, Julius Otto Grimm, and Bernhard Scholz, signed a declaration distancing himself from the artistic maxims of the New German school. To be sure, the document was only intended for internal use, but it was passed on to a Berlin daily newspaper and published there – with Brahms' name at the top of the list of signers.

This, too, did not yet have anything to do with music – but already with music history. For until the publication of this document, the New Germans had to define their opponents themselves; an unsatisfactory scenario for the controversy among aestheticians that they hoped to initiate. With the appearance of the "declaration", there really was an opposition that came out into the open as a group and let itself be provoked: without its own program, without the desire to get involved in the dispute with pamphlets and manifestos.

And the dispute created an audience – especially for the New Germans. Back in conservative Graz, Herzogenberg was able to make a living as a freelance composer. His new compositions were almost always premiered to great success, for instance the dramatic cantata Columbus for soloists, men's choir, mixed choir, and large orchestra op. 11, that Friedrich von Hausegger, in turn, acclaimed as a modern, Wagnerian work:

"...that the composer displayed not only the will, but also the power to break completely with dated traditions, and lend his work the only remaining viable form; that he – let's not beat around the bush – revealed himself as a follower of the musical direction represented by Richard Wagner."

The successes came too easily for Herzogenberg. In 1892 he moved to Leipzig, but met there a musical culture that was so conservative that a life exclusively as a composer was no longer possible. Alfred Volkland, the chairman of the Leipzig Bach Society, and Bach biographer Philip Spitta organized a job for him with the Bach Society, and later his assumption of the position as music director. Acquaintance quickly became friendship: Spitta arranged for performances of Herzogenberg's compositions, although only in the more progressive musical associations; in the thirteen years between 1872 and 1885, the Gewandhaus Orchestra presented only one Herzogenberg performance.

As his last Wagner-oriented work, the twenty-nine-year-old Herzogenberg composed the symphony Odysseus for large orchestra op. 16. This was then followed by a break with his own works. It is not known what caused Herzogenberg to make this about-face, but its beginnings are apparently to be found in a conversation with the conductor Franz Wüllner. In 1872 Herzogenberg worte to Wüllner: "This molting had its beginnings in Schliersee, and you were its author, intentionally or not. Last year it was then the even closer acquaintance with Brahms and in this winter the founding of the Bach Association that continued the cleansing process and finally brought my feet onto solid ground."

An almost three-year pause in his publications followed, which was ended in 1875 by the Piano Quintet in C Major op. 17. The Piano Quintet is the first work of Herzogenberg's new creative period, a period that was not oriented on Wagner, but on Brahms. So strongly oriented that already in 1876 Herzogenberg described Wagner as "hostile" – a "Brahmsian" right out of the music history book.

It is not only a piano quintet that Herzogenberg composed as the first work of the new period, it is above all a chamber music work. For composing chamber music can certainly be an ideological gesture. In the New German camp, one scorned chamber music as conservative, antiquated, as the epitome of a reactionary understanding of musical aesthetics. To compose chamber music in spite of this could thus only mean opposition. And for Herzogenberg, taking a stand against Wagner was the same as taking a stand for Brahms. Also in the further course of his compositional activities he was to devote more attention to chamber music than to other genres. It remained the favorite subject of discussion in his correspondence.

Not everybody noticed the gesture of the Piano Quintet. One knew Herzogenberg as a progressive composer, and the quintet, too, had to submit to this assessment. "Finally someone who once again dares not to write a sonata-allegro movement!" ascertained Hermann Kretzschmar. Yet only with effort, since it is actually only the monothematism of the theme groups that are unusual: the sonata-allegro form is there, but not the daring.

From 1875 onward, Brahms played the main role in Herzogenberg's compositional life, both in person and in correspondence as well as musically: as a model, not as a template. Because a Brahms follower is not necessarily a Brahms epigone. Herzogenberg learned much from studying Brahms' scores. Some things he rejected, for example, the characteristic motivic treatment. Other things, such as the harmonic colorfulness of Herzogenberg's development sections, cannot be traced back to Brahms, but rather to early Herzogenberg, with which the later Herzogenberg does not want to have any thing to do.

The result of all these influences, however, has to bear the comparison to Brahms. "For thirty-five years I've asked myself with every note head: What would Brahms say about it?" he admitted with disappointment. Disappointment because Brahms never answered. A copy of almost every composition was sent to Brahms with the request for an opinion. Brahms avoided committing himself. But he was more open toward others, for example, his former Viennese piano pupil Elisabeth von Stockhausen, whom he passed on to another teacher in 1862 under more or less delicate circumstances, and who married Herzogenberg six years later. For Brahms, Elisabeth played a role similar to that of Clara Schumann's. Brahms admitted to her that, almost without exception, he did not like Herzogenberg's works.

During the course of his "molting", Herzogenberg had shed Wagner more thoroughly than Brahms could have really wanted. Since Schoenberg, at the latest, we know that Brahms was not as conservative as he had been accused of. In particular, the preliminary stages of the "developing variation" that Schoenberg found in Brahms had a innovative potential on a par with the musical ideas of Wagner and Liszt. Through this connection to Brahms, Schoenberg was also finally able to turn the ideological role of chamber music inside out, which for us today is considered the epitome of a rejuvenating genre. It was these "minor details", these peculiarities that literally go beyond the pure music that Brahms found lacking in Herzogenberg. It remains to be determined whether he just overlooked them.

And thus, the progressive element in Brahms is not in the renunciation of the sonata-allegro form, as Kretzschmar assumed in Herzogenberg, but rather in its realization. Both outer movements of the Piano Quintet in F Minor op. 34, by Johannes Brahms, are in sonata-allegro form, have at least a similar structure, and display especially the motivic-thematic treatment that for Schoenberg constituted the progressive in Brahms. Here, too, the sonata-allegro movements are modified, the contrasts fundamental to them first be have to created out of the basic material and develop into a diverging fabric of motives, themes, and ideas.

Many an author has called the F-Minor Quintet Brahms' greatest chamber music work. Clara Schumann even came to the conclusion that it was too great for a piano quintet and that "the ideas should be spread throughout an entire orchestra". For all that, it did not start out well. In 1862 the work was finished in its first version for string quintet. In at private performance at Joseph Joachim's in Hannover, it disappointed all the participants. Brahms recast the quintet as a sonata for two pianos, which he performed in 1864 at a public concert of the Vienna Singakademie. Again, it was not a success. Only the synthesis of the two unsuccessful versions, only the combination of string ensemble and piano made the composition world famous.

Like Herzogenberg, Brahms, who was ten years his senior, had been in Vienna since 1862, the latter as piano teacher, freelance pianist, and director of the Singakademie, the former as a student at the Conservatory. Brahms, who never attended college, suffered his whole life from his lack of a general education, and he later considered Herzogenberg, in particular, to be the model of an educated man. Whereas, after his studies, Herzogenberg was able to live from composing, Brahms had to give piano lessons, for example, to Elisabeth von Stockhausen, whom Herzogenberg met around the same time, and who twelve years later, in 1874, organized a Brahms festival in Leipzig through which the contact between the two composers was finally cemented. A meeting that had many consequences: besides the beginning of an intensive correspondence, Herzogenberg referred to it as a further starting point for the "molting", whose first result was, as we know, the Piano Quintet.

Brahms established himself in Vienna, so that he was soon able to give up teaching, and live as a freelance composer, although he would have preferred a regular position in Hamburg. He hoped for the direction of the Philharmonic Society in Hamburg. When the position was given to somebody else, he became embittered: "Had one chosen me at the right time, I could have become a respectable man, I could have married and lived like everybody else. Now I am a vagabond."

There was a simple reason why he did not receive the position in Hamburg: He had not applied for it, but rather hoped that the Hamburg authorities would approach him. In any case, the possibility for the position as conductor of the Vienna Society Concerts came up in 1872. Brahms accepted, but relinquished the post three years later; he was not made to be a conductor. Never again in his life was he to assume a position.

In 1876 Brahms finished his First Symphony. The conservative made an attempt at orchestral music, the domain of the New Germans. It was not his first orchestral work; two serenades, a piano concerto, the Variations on a Theme by Haydn, and several works that he later destroyed had already been composed. But only with the First Symphony did a crossing of a border, in the sense of the New Germans, take place. Three further symphonies followed within a period of nine years. Wagner, who became aware of the twenty-year-younger Brahms, wrote ironic commentaries about and damning criticisms of the "strange moral watchdog of musical chastity", whose works he slandered as "deception".

In spite of this, orchestral music remained only a small part of Brahms' oeuvre. The number of piano and chamber music works amounts to four times that of the orchestral music. None of the symphonies carries a dedication, in contrast to a majority of the chamber music works, for example the forty-six-year-old composer's Rhapsodies op. 79 – written in a sudden wave of youthful exuberance – which were to be dedicated to Elisabeth von Herzogenberg in 1879. The request for the dedication was no less exuberant: "...will you allow me to put your lovely and honored name on this little thing? But how is it spelled? Elsa or Elisabeth? Freifrau or Baronin? Maiden name or not? Forgive this stupid youth everything possible, but send word as soon as possible, and namely to me in Ischl..."

The Herzogenbergs were also the first to get a look at the Fourth Symphony in 1884, before the new work was tested, in accordance with Brahms' custom, on two pianos in a circle of friends. Almost every one of Brahms' works went through this "test phase". In the case of the Piano Quintet, the testers were Joseph Joachim and Karl Tausig (a supposed "New German"); later it was increasingly often the Herzogenberg family that had to give the first commentaries about Brahms' new compositions.

Although the examination of Brahms' Fourth Symphony on 8 October 1884 certainly did not come at an opportune time for them. Only a week earlier they had moved to Berlin, because Heinrich had accepted an appointment as professor of composition at the Berlin College of Music. Spitta had interceded for Herzogenberg, since the then professor, Friedrich Kiel, had not been able to carry out his duties since 1882 as a result of a severe illness. Kiel, however, did not relinquish his position, so Herzogenberg could assume it only in 1884, after Kiel's death.

Already in 1887 a rheumatic condition forced Herzogenberg to take a leave of absence, and in 1891 to give up the position. His convalescence suffered a set-back through the death of his wife the following year. The fifty-year-old Herzogenberg lived as a freelance composition teacher in Berlin, worked temporarily for the Vierteljahresschrift für Musikwissenschaft, in the editorial commission of the Denkmäler deutscher Tonkunst, wrote expert's reports on various musical matters, and directed, from 1892, the Berlin Musical Society.

On 1 May 1897, three weeks after Brahms' death, Herzogenberg was for the second time appointed to a professorship at the College of Music, but the ailment broke out again. Once more he was prevented by treatments and spas in various towns from performing his teaching duties, which he again gave up in 1900. Herzogenberg died that same year while taking a cure in Wiesbaden.

In the last years before his death, Herzogenberg began writing a harmony textbook, of which only one chapter, with the title "Tonality", was completed. The chapter was intended to allow a glance into the composer's workshop. However, he never called tonality into question, and concentrated on the terms "triad" and "key". It is still the pamphlet of a traditionalist. Yet, time passed it by. The New Germans were active for twenty-seven years, until their leader, Liszt, died in 1886, three years after Wagner. Debussy, Satie, Schoenberg, and many others let their aesthetic dispute become stale. It simply petered out, without a solution (which was indeed never desired), without real historical consequence. Only, musical historiography sometimes still plays its pranks with it.

Jörg Siepermann